As I prepare for the inaugural Moving Balkans showcase, a fellow dance journalist asks me to say some words about ‘Balkan identity’ for a podcast episode produced on the festival. I hesitate. The question feels impossible to answer. I sense that whatever I end up saying will gain disproportionate weight. Most outsiders I encounter seem to have firmer notions of what Balkans means than I have managed to establish, even though I’m born in Novi Sad and hardly put a foot outside the region before I turned 20. From the outside, the Balkans may appear like an exotic ‘other’ at the periphery of Europe (albeit one that keeps playing weirdly key roles in various historical events). From the inside, Balkan identity, if it exists, feels personal, fractured, and deeply contradictory.

Little wonder I was looking forward to this first showcase of the Moving Balkans platform, a ‘new dynamic collaboration of dance professionals from across the Balkans’ established in 2024. The festival took place over four days in three cities, Ljubljana in Slovenia, and Rijeka and Zagreb in Croatia. Would I find trace of something uniquely Balkan in the approaches to contemporary dance? Or would I only find exposed the scarce resources and difficult conditions faced by artists across the region?

Pressure and transformation

Life is a grind (in the Balkans as everywhere else). In Runway, the opening piece, Christiana Kosiari (GR) takes this literally. Standing on a treadmill through the entire performance, Kosiari never stops moving forward. As a metaphor for the suffocating societal demands for beauty and perfection, it is pleasantly straightforward. The stage is lit by cold blue neon tubes which frame the dancer dressed in sneakers and sportswear as she keeps running the endless race for self-improvement imposed on women. The performance is direct and to the point, just like scrolling through TikTok videos on beauty tips and ‘life hacks’. Yet while Kosiari initially has the air of a narcissistic fitness influencer, soon the cracks start to show. She gradually undresses and covers herself in black tape in a repetitive, obsessive mapping of her body. With each gesture, magnified by Jan Van Angelopoulos’s beats, the stakes heighten and the performance intensifies.

Completing her metamorphosis from jogger to a dead-eyed catwalk model strutting in stiletto heels, her facial expressions keep shifting between fear and exhaustion. As a reflection on the vicious circles of shame and sacrifice that shape how female identity is constructed and consumed, Runway delivers. Yet the metaphor’s simplicity is both a strength and a weakness. From the first scene we already know all too well where we are heading, and for all Kosiari’s efforts (her own very real strain) the performance offers no alternative model.

It would soon be clear that such a lack of prospects for viable alternative futures would form a gloomy backdrop to the festival.

DILF by Marko Milić (RS), performed by Svetozar Adamović, is a quieter, yet equally confrontational meditation on queer body politics. The stage is minimal, the performer nude, oscillating between a Rodin-like statuesque stillness and in-your-face muscular bodybuilder swagger. His exposed penis acts as both erotic symbol and uneasy emblem of power. He repeats subtle micro-movements: bending and touching himself sensually. Beneath, one senses glimpses of tenderness, especially viewed through a psychoanalytical lens of shame and self-discovery: where ‘strong fantasy’ triggers a ‘trauma’. Nonetheless, the tension slowly disperses as the desire becomes abstract and conceptual. The monologue leans too much into cliché, jumbling between obscurity and introspection. DILF wants us aroused and unsettled but too often leaves us on the outside, unable to fully engage with a self-centred exploration of identity. We watch ourselves watching, as the seconds slowly tick by.

Gong by Filiz Bozkus Al (TR) invokes the four elements for a journey of self-discovery rooted in Butoh. Beginning with embryonic, crouched movements, it later devolves into exaggerated, childlike gestures. It is true, we are witnessing a cycle of life, where death and danger creeps from every corner, corrupting the naivety of childhood. Still, the piece remains hovering in a liminal uncertainty, too theatrical to invoke the rawness of ritual. Despite moments of frank enthusiasm, the promised Butoh never fully materialises, rather ending up as a seemingly unintended parody.

Porous co-existence

While some pieces focus on the body as individual identity, others challenge the notion of individuality and the body as a self altogether.

In BLOT – Body Line of Thought, by Simona Deaconescu and Vanessa Goodman (RO/CA), the body itself becomes a stage for a porous process of negotiation between skin and senses, the salt in our sweat and the microbes in our gut. The white stage is a space of ostensible scientific neutrality, and unlike DILF, the two nude performers are not eroticised; their bodies are systems and materials to be explored. A mountain of salt looms in the background. A screen shows cultures of bacteria growing on agar plates, like microscopic countries expanding their borders on an empty map. The bacteria are the unlikely heroes: they influence emotion, give us health and immunity, and they are crucial to life on earth. One performer jumps rope while the other recites seemingly random facts: ‘6 metres – the length of the small intestine’ … ‘More bacteria in the gut than stars in the Milky Way’ … ‘At this moment, my heart rate is 97’. The data is objective but incomplete and intimate. They move around the stage in solitude, but the rare touches leave a lasting impression, showing how identity and self leak beyond skin. BLOT leaves us with the quiet, destabilising awareness that to be human is to be plural, between sweat and breath, with the bacteria constantly growing and moving to the passing rhythms of time.

A similar presence of life as complex, dirty constellations of matter hovers over Saline Nebula, a collaboration between Stanislav Genadiev and Violeta Vitanova (BG). An insectoid dancer is curled in foetal position, coated in sugar like a second skin, on a table at the centre of stage. Her movements are staccato, tactile, as if navigating an alien terrain. Her limbs are cracking and flexing. Verticality seems unreachable. It’s certainly an atmospheric piece – obscure, hermetic, shiny – marked by loops of instability and fatigue; a dreamlike experience of a foreign body negotiating its own limits in a fractured world. As sugar dissolves in a liquid substance, Vitanova crawls out of the frame of our sight. It resonates with our current time, but, unlike the careful and elaborate steps and progress of BLOT, Saline Nebula lacks in dynamism. The imagery intrigues, but the piece has potential for deeper development.

Spectacle, excess, and the digital age

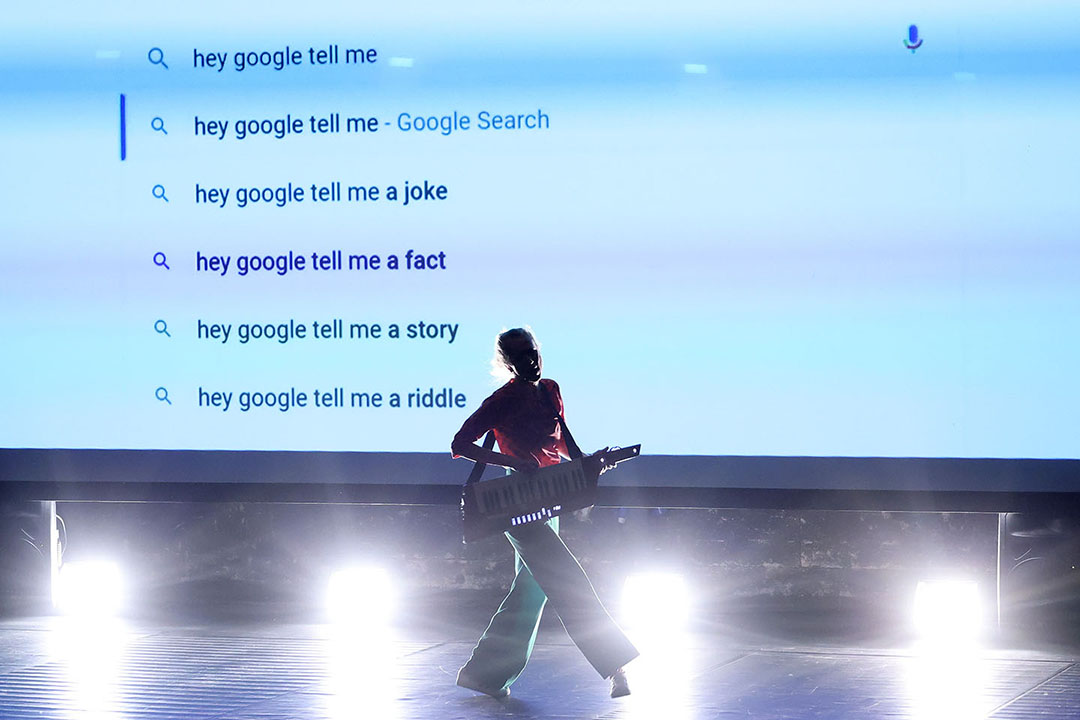

Yet it’s not all about bodies and materiality in the Moving Balkans showcase. Arguably, virtuality and the shallow and depressing temptations of contemporary life play an even more central role. One clear highlight is Screenagers Vol. 2 by Barbara Matijević and Giuseppe Chico (HR/IT), one of the festival’s most coherent works. A massive screen and a hybrid guitar-keyboard set the stage. A childlike voice narrates a bedtime story: as the cable that connects the internet worldwide is chewed over by a fish, people are left helpless. What is to come is a satire about digital dependence. The performance mixes movements, music, memes, and intergenerational cultural references. Selfie culture meets the cosmic glitch.

The performer’s voice captivates and the audience has to compete in game-like challenges. Even a simple task like making Super Mario jump becomes difficult when done collectively. The improvised finale – prompted by ChatGPT’s inconclusive suggestions – becomes a communal moment that invites the audience to co-create the ending, embodying the festival’s embrace of uncertainty and shared survival in the digital age. The joyously pessimistic final refrain is somehow defiantly hopeful: ‘the show must go on, flying to the great unknown’. As bright and happy as it is on the virtual surface, it is the irony of the dark reality outside our screens that makes Screenagers Vol. 2 a work that is hard not to like.

Other works go all in on camp and clubbing excess. Masterwork for Six Dancers, by Emese Cuhorka and Csaba Molnar (HU), blends voguing, burlesque, and slapstick. Painted bodies twitch to techno beats in a cultural mashup, from Bauhaus to drag balls. It’s both a wild parody and a homage. Yet the performance’s relentless excess collapses into an ungratifying indulgence that obscures any potential critique. Ultimately, the theme of individualistic (neoliberal) self-expression that haunts so many performances here leads to a jumbled spectacle. Patricia Apergi’s (GR) The House of Trouble continues the trend of indulging the freakish and unusual. A stage surrounded by reflective, cushion-like balloons becomes the scene of a fashion-slow-motion rave party. Performers in crocs and corsets move in a catwalk across the stage, each part of a imperceptibly changing tableau: a headless cake-body, an octopus-man, a swarm of limbs, pistol-flowers, long soulful embraces. It teeters on human zoo aesthetics, shouting: ‘Buy me, have me, use me, I’m under extinction’. With dancers sweat-slick and grinning under the synthetic fog, it feels like a never-ending, ever-changing purgatory.

The title of the next performance promises a badly needed respite from all that is ‘wild’ and ‘crazy’ (yet somehow conspicuously tame). Indeed, Silence by Linda Kapetanea and Jozef Fruček (GR), begins promisingly: a stage submerged in white fog, a soldier-like figure barefoot beneath a spotlight, confessing his life story like Samuel Beckett’s forgotten son. ‘God demands to burn all my flesh,’ he says, trembling and moving his hands expressively. Five men emerge and conjure waves with ropes. A hooded woman appears, cradling a black pillow. Nuns circle around us. The silence here screams louder than the avant-garde noise erupting later. Trauma is her face. Dancers become corpses, objects, masses. Limbs clash, layers of material fall – purple into black. Someone’s being punished or saved. A woman’s body bends like a question mark. A man is bagged and dragged away. Strobe lights convulse. Catholic guilt slithers in, or is it my imagination. I leave the theatre in a fantasmagoria of doubts.

The final performance of Moving Balkans, Simone Aughterlony and Sasa Božić’s (CH/HR) Agenda, equally drowns in relentless dancing to stave off our existential dread. As we enter the theatre space, dancers are already bouncing to the club beats like a chaotic swarm of youths at a nightclub. Joyful rhythms and playful movements are the leading lines of this work, but mostly, they are spellbound by the murmuring promise of an ecstatic dancing experience. Their bodies shift between urban dance, hip-hop and free improvisation, radiating a warm, communal energy. Some of them are glittering in casual clothes, others are more extreme, following fetishist aesthetics: high heels, whips, orgies on sand. A lying naked woman spits black liquid, evoking Courbet’s L’Origine du Monde. The visceral imagery clashes with the repetitive choreography. The piece ends as it began: a wild, unfiltered outcry.

What does all this mean?

Moving Balkans proved a mixed bag. The performances often felt familiar, rehashing well-worn themes without fresh perspective. Here, as everywhere else, the response of contemporary dance to the challenges of contemporary life is too often limited to euphoric escapism. Here, as everywhere else, this imperative to dance like crazy rarely truly affects the audience to join in. Any watchful eye will observe how quickly this carefully staged bacchanal excess takes the form of a sort of defiantly happy nihilism or a mirthless dance to drown our sorrows.

Yet what was I really expecting? In my notebook I wondered: ‘Does art obey the simple laws of economics?’ Can we trust that great artists and great art will rise through the cracks, like a dandelion through asphalt, or does a thriving art scene require careful nurturing like a sensitive orchid? The answer from Moving Balkans is clear: while some dandelions flower despite lacking funds and opportunities, some flowers still require time and care to bloom. With cuts and attacks on radical art increasingly prevalent across Europe, it appears that, as so often before, it would be prudent to pay heed to what’s moving in the Balkans. ●

Ljubljana (Slovenia), Rijeka and Zagreb (Croatia)