The greatest piece of this year’s SAAL Biennaal was one I didn’t see. It was a piece that was performed at the very same festival 18 years ago. It was a piece called Frans Poelstra, His Dramaturge and Bach… But more on that later.

Founded in 1999, SAAL Biennaal (formerly August Dance Festival) is Estonia’s longest-running contemporary performance festival. Over the years it has experimented with different curatorial models. This edition was the second to be collectively curated by the ten members of Kanuti Guild Hall. Technical managers, project coordinators and curators all had an equal say. None of them had seen the full programme performed live before opening night – the line-up was built on trust. Would such a method generate a festival buzzing with synergy, or result in a ‘best-of’ or all-star line-up?

Choosing a concept that lands, and milking it till the last drop

Surprisingly, the programme wasn’t filled with collage-like works of quickly altering eclectic scenes stitched together in a TikTok rhythm (a common trend elsewhere). Instead, many pieces pursued a single idea that was extensively explored on stage. The opening night set the tone with a double bill of Sepideh Khodrahmi’s The Erotic Clown and Xenia Koghilaki’s Slamming.

Sepideh Khodrahmi produced, seduced and finally abused a cake all by themselves. The theatre’s bar area swarmed with the excitement of a festival opening and post-summer reunions. A glittering character entered the chatter in tight blue jeans with sparkling cut-outs at the buttocks and a pink top, smizing eerily. They carried an over-the-top whipped cream cake decorated with plastic butterflies, parading through the crowd before setting it down as the main character on centre stage. The seduction continued as Khodrahmi shifted between club dances, voguing, twerking and contrasting it with something from somatic practice. The show was building towards a climax one could sense from the very entrance. Ultimately, yes, they sat on the cake – more precisely, did the splits on top of it, smearing cream across the stage. As they exited, they offered bites to select audience members. I got the taste, it was sweet. Perhaps even too sweet…

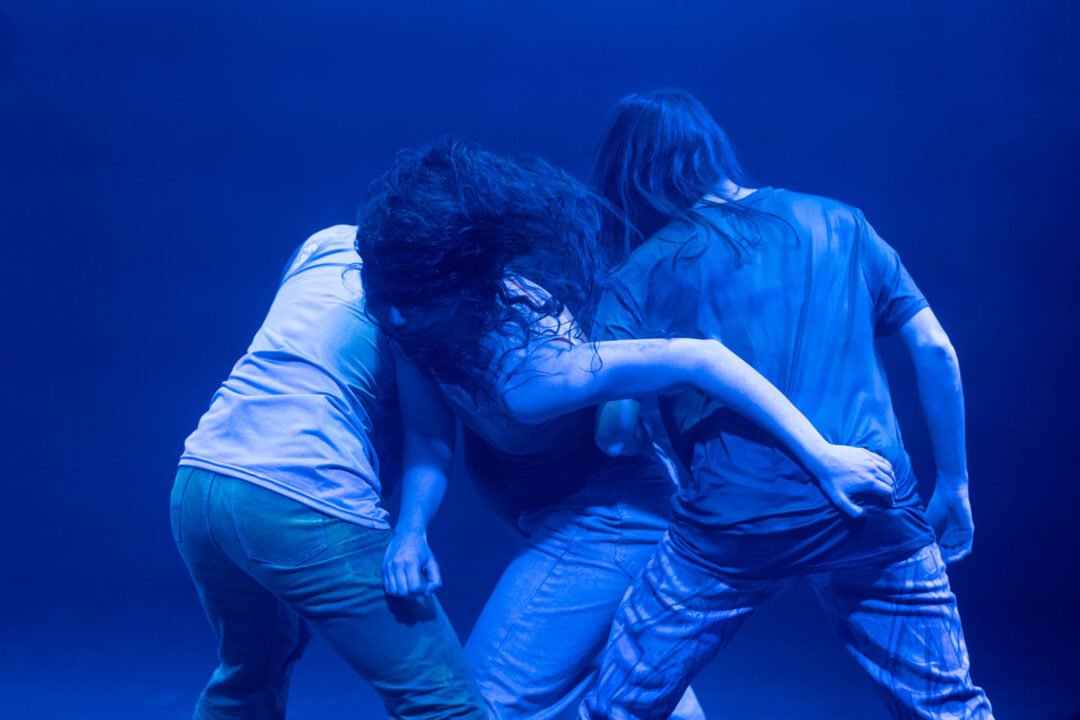

Xenia Koghilaki’s Slamming had a similar single-concept approach (revealing its idea to the audience from the very start and exploring it throughout) but was more eloquently packaged. Three tall slender figures in jeans, tops and sneakers – everyday raver attire – began headbanging. Their dark, unbound hair whipped through the space like flames, conjuring mirages of magical creatures. It was indeed refreshing to see a work that was clearly choreographed yet felt improvisatory. Through constant headbanging, the performers found delicate compositions, climbing over or hanging onto each other. They became a warhorse, a pivot swing, a living flame – as they moved seamlessly through the scenes. I didn’t notice when or how they had removed their shirts, and marvellously, I felt every change slipping through my fingers. But I wanted to hold on, to catch their rhythm, as their hair at times struck golden cymbals, adding a sharp edge to the culminating piece.

One evening, a bus took us to a lush green forest, through which we quietly hiked to a slope near a meadow. It was green, it was warm, it was peaceful, and it smelled nice. One by one, these ‘exotic’ creatures of Harald Beharie’s Undersang appeared, clad in black leather, breathing loudly, seeking connection with both the audience and the surrounding serenity. Gradually, their voices grew louder and more intense. Step by step, they became more courageous, moving closer and closer. At one point, they stood with eyes bulging, saliva drooling down their chins onto the laps of the audience, bits of moss and branches clinging to the skin, while their heavy groans echoed with the pulse of a techno beat. The piece didn’t completely convince me of its potential commentary on the notion of ‘exotic’ and how we as white viewers perceive it. Yet I was intrigued by their choice to perform for a seasoned, almost elitist audience. It is not really a performance to suggest to friends and family… But perhaps its narrow audience is its very target.

Stories, stories, stories

Another category that emerged from the festival was story-telling performances. While some shows leaned heavily on narration, they still played into the earlier tendency towards one clear idea carried through to the end.

Choir singing is a fundamental part of being Estonian: every two to three years tens of thousands of singers join in the national Song and Dance Celebration. But we don’t really have a culture of musical theatre, especially musicals. Hence, Icelandic directors Ásrún Magnúsdóttir and Alexander Roberts’ Teenage Songbook of Love and Sex with a local cast had a compelling context to work within. The songs sung were sincere, unpolished, and not really built for critique, but they delivered exactly what the title of the work promised. The same applied to the performers, who were young and full of energy, and seemed to genuinely enjoy being on stage. As a youth project, I could value its impact; as a theatre performance, it convinced me less. The whole piece floated somewhere in between a concert at a camp, a worship at a gospel, a ceremony at school and a performance you put on for your parents at a sleepover. Still, the stories rang out – loud, simple, and clear.

From one story to another, I stepped into one of the most magical ‘non-performative performances’ I’ve had a chance to see. In Cognitive Maps, Ely Daou, a performance artist from Lebanon, welcomed us into an informal theatre space to sit on pillows and chairs surrounding him. He himself sat in front of the analogue projector from which he projected floor plans of the apartments he had grown up in. He shared stories from his childhood and adolescence, all the while drawing lines and tracing memories on top of the plans. Like seeing his grandma from around the corner or trailing a line of his blood caused by one of his childhood injuries. Through introspective memories he also told the history of Lebanon from late 1980s to early 2000s. As I left the performance I was caught off guard wondering what actually had worked… There was no stage presence, his voice was hard to follow, and there was no spectacle or theatre magic. Yet I was drawn in completely.

Another deeply personal non-performative experience was Bush Hartshorn’s Tell Daddy bordering between a therapy session, a tender conversation with an acquaintance, and an experience that can only be lived…

At times less words could also be impactful. It was a rainy Saturday afternoon as we marched to a closed-off industrial port to see Asphodel Meadows by Sinna Virtanen. We were then directed to put on waterproof fishing pants, silvery reflective hats and wireless headphones. As soon as I put the headphones on, a calming soundscape immersed me. Finally we reached a sandy beach with a panorama of Tallinn, my hometown, yet from a perspective I’ve never had a chance to look at it from. The sea crashed onto the shore harder as the cruise ships passed by the gulf to the harbour. The sun started to peek through the rain, while the city still had heavy showers. The two performers Malou Zilliacus & Geoffrey Erista walked mesmerically through the sea to the dock, where they dressed themselves ceremoniously in white. They headed back to the sea, only this time they invited us to join them. It was all so beautiful…so beautiful, that I barely registered a word they were saying (though apparently, they talked all the way through).

A few outcasts that intrigued

Gob Squad’s new production News from Beyond landed somewhere between the last two categories I’ve been exploring. On the one hand, it had a clever premise: collecting questions from the audience and going outside (the streets of the old town) to search for answers. Blending the line between staging and chance, objects and people (both voices and bodies) from this outside emerged on stage and became the backbone of the piece. Yet the aesthetics were off. The costumes that looked like they were from costume rental, the standup-ish delivery, and the almost naive sound design reminded me of school productions. It worked as off-beat entertainment first and foremost – and maybe, if one tuned in hard enough, something deeper from the outside was there too.

A more polished outcast was Ramona Nagabczyńska’s Silenzio! which started with a fascinating game of mimicry. Four performers (opera singers, we learned later) stood at the front of the stage, locking eyes with the audience. When they caught someone’s gaze, they amplified the reaction they received and reflected it straight back. At some point they found their voices, and then the whole building buzzed with screeching notes of alarm sounds created by Katarzyna Szugajew, Karolina Kraczkowska, Barbara Kinga Majewska, and Nagabczyńska. The image was unforgettable: four women in heels hurling mattresses across the stage, leaping and collapsing onto them, then surging up again and bolting to the next one, their cries piercing through a stark yellow light. Still, for all its power, in the context of this festival it felt curiously out of place.

There were two shows by Estonian artists that created a dialogue between them. Netti Nüganen’s Ash, horizon, riding a horse was a collage piece, mixing mediums of sculpture by working with ice, physical theatre, banjo music and live painting on melting ice – actually functioning more in the realm of performance art in visual arts than theatre. Mart Kangro’s Pantheon, however, clearly worked with the format of theatre but the content was cultural-historical – challenging the viewer to consider how we read cultural codes and signs, how influenced these are and how aware we even are.

And so to the greatest piece of the festival, that I didn’t see: Frans Poelstra, His Dramaturge and Bach, performed here 18 years ago. Its first scene has now been re-created in Michikazu Matsune’s All Together… Poelstra stood naked with his back to the audience, swaying from side to side, as Matsune narrated his first experience of seeing him on stage. Over 65 minutes Poelstra, Matsune and Elizabeth Ward reminisce about the people who could not make it to the performance, while simultaneously creating a universal story-telling piece. So simple and minimalist in its nature: three bodies on stage, three white chairs on stage, three kinds of humour – but they won the hearts of the audience, as we laughed along with their absurd, interlinked experiences of people who share the same names.

So, was it a best-of? Hardly. It was something more intricate: a festival where the works resonated with each other, where storytelling and one strong concept became the threads tying the programme together. That was the format. And the content, no less direct than the slogan on the staff t-shirts, was simply: It’s per-so-nal. ●

21–31.08.2025, Tallinn, Estonia